Electrocuted? Clarifying Terminology!

“You keep using that word. I do not think it means what you think it means.”—Inigo Montoya, The Princess Bride

Electrocuted? Clarifying Terminology & Being Vigilant About Electrical Safety

I originally wrote this article for musicians on live music stages, but it’s the same terminology and safety precautions for RV owners.

What’s in a Word?

“You keep using that word. I do not think it means what you think it means.”—Inigo Montoya, The Princess Bride

Electrocuted?

The TwitterVerse (X-Verse?) was hopping a while back with news of Canadian singer Grimes being “electrocuted” during a concert in Dublin. (Go here and #Grimes on X.)

OSHA Definition

According to the Occupational Safety and Health Administration (OSHA), “electrocution is a fatal electrical injury that occurs when a person is exposed to a lethal amount of electrical energy”.

While she was shocked on stage, she definitely wasn’t electrocuted multiple times. That’s because the word “electrocution” refers to death by electric shock. If she was indeed killed by electric shock and brought back to life multiple times to keep performing, that must have been one heck of a show. Sort of like Frankenstein’s monster playing backup keys for your band (now that’s a show I would pay to see).

So how did we get here?

Mostly, it’s the media. Not a day goes by that I don’t read or hear some misuse of words about electricity in both mainstream and alternative media. Whether it’s a TV report about street poles with “current on them” that spark when rubbed with a screwdriver or reporting about being safe from lightning striking a car because of “rubber tires insulating you from the ground,” it’s just plain incorrect information that feeds the “urban myths” factory.

To set the record straight, we are quite safe from lightning strikes in our (non-convertible) vehicles due to the Faraday Cage created by the car metal surrounding us. That’s what bends the electricity around the occupants, keeping them safe if a lightning bolt hits the vehicle. Of course, you don’t want to have your hand stuck outside the window in a lightning storm, because you’re no longer inside the cage and you’ll likely be electrocuted. And yes, I mean killed by electric shock.

What happened?

So what did happen to Grimes? Well, there must have been something on stage that wasn’t properly grounded. (The report linked above attributes the cause to a “malfunctioning pedal.”) The lack of electrical grounding allows a normal AC power leakage current to create a voltage bias on a piece of gear (guitar, keyboard, microphone, etc…).

If you get between this electrically “hot” gear and something else that is properly grounded, that’s when you feel a shock. Depending on the voltage, how wet your hands are, and the source impedance of the fault current, you’ll either be shocked, knocked unconscious, or possibly even electrocuted (again, killed by electric shock). Check out this drawing for a real 18th-century experiment about feeling electrical shocks:

So how do we check for this invisible electrical danger?

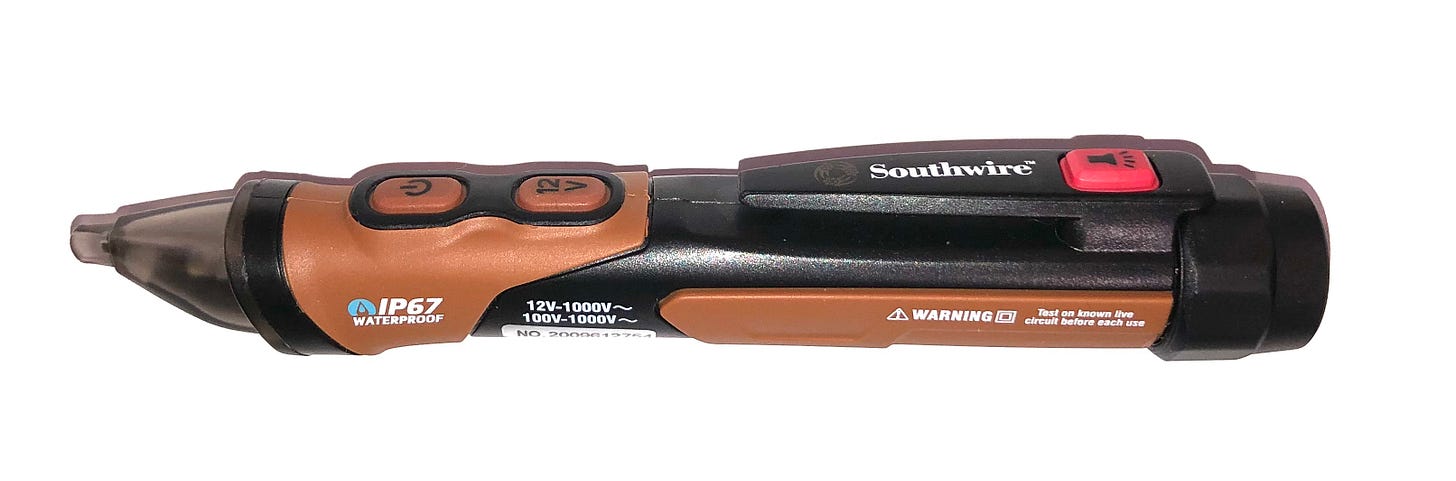

Well, a device called a Non-Contact Voltage Tester (NCVT) that can be purchased at any big box store for less than $20 provides a quick way to test for hot-skin voltage.

And properly installed GFCI receptacles have and will save lives. So don’t bypass them if you encounter one. And if a GFCI trips, that’s an indication that something has gone wrong with your RV or appliance and dangerous voltages are possibly on the loose.

Just be aware that any electric shock is proof that a safety ground wire has failed somehow and is allowing dangerous voltages to appear on your gear. So if you feel a shock from a guitar, electrical appliance or your RV (any kind of shock), then it’s time to find out the reason and get it fixed immediately.

And if you hear or read a reporter discussing how someone was “electrocuted” at a concert or campground but is still alive to talk about it, contact the media person and/or organization and refer them to this article. I think that we all get way too complacent about electrical safety when we should really be more careful. Few campers will ever put themselves in the dangerous positions that performers and sound technicians find themselves in every day when they’re surrounded by all sorts of electrically powered gear.

Let’s play safe out there… Mike

Way back in the day before amps had 3-prong plugs, and after experiencing the wonderful (!) feeling of electricity on my lips when I went to the mic to sing, I always brought a voltmeter to practice and gigs and tested the whole stage before we started to play, and did the “plug flip” when voltage was present. Sheesh.

Mike, your article made me think of a situation where I had to change to a non-GFCI outlet because of nuisance tripping. I have an electric gate opener that opens and closes a metal gate in front of my driveway near the street. The house is in a rural area and we have a lot of power outages. Most all gate openers like this have a small 12V battery that is maintained at full charge by a wall plug-mounted low voltage power source. I’ve seen both 12-24 V AC and DC used in my 20 plus years of working with gate openers. One day, my gate would not open and after a bit of troubleshooting, I found that it’s lead-acid battery voltage had dropped to 11.5 volts and determined by testing that the gate opener had shut down. I assumed at first that it was a bad battery but found by looking at the date tag that it was only a few years old. The lawnmower batteries I use normally last for 3-5 years, so I did not just replace it. Instead, I started measuring voltages and found there was no voltage coming from the power source. The plug-in power source was mounted inside of a building 100 feet away from the gate. I eventually figured out that the inside the power source was plugged in to an outlet that was daisy chained to an outside GFCI receptacle that had tripped during a past power outage. I had not noticed it because I use that outlet very rarely. Gate opener batteries are sized to open and close a gate many times on a single charge. So, the gate didn’t die for quite some time (days) after the GFCI had tripped. After thinking about this situation, I decided to use a non-GFCI outlet for the gate opener power supply because its output was low voltage DC and would not present a shock hazard even if a fault were to occur. I’d prefer to have left the power supply on a GFCI outlet but having the gate opener fail while I’m away was not an option I could live with. I need the gate to operate reliably even when I’m not there for extended time periods. I’m wondering if you or other readers have had any similar experiences?